AP

The eternal amorist Mohan Bhagwat at an RSS meet in Bangalore

ESSAY: HINDUTVA

The Morality Tale That The Mahabharata Just Isn’t

Its epic transgressions surely cannot be the underpinning of the Sangh parivar’s Hindutva

The new chairperson of the Indian Council of Historical Research (appointed by the BJP-led government), Yellapragada Sudershan Rao, has promised to push research projects to rewrite ancient history based on the stories of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. According to him, they are truthful accounts of historical events. But he should be careful when choosing the epics.

The stories of the Mahabharata, for instance, are often at odds with the Hindutva that the BJP government and its parent Sangh parivar preach. Although the votaries of Hindutva worship the epic’s heroes and heroines, the messages that most of the latter impart may not be suitable for the present government’s programme to educate our people in the “moral and cultural values” that they want to uphold in the name of Hindutva. In fact, the deities and mortals described in the eighteen volumes of this hefty tome had never once been designated by the term ‘Hindu’. The Mahabharata may turn out to be a rather uncomfortable quarry for the BJP ministers and Sangh parivar historians to dig up models to suit a Hindu-specific Indian ideal of morality and culture.

The just-replaced health minister Harsh Vardhan (a medical practitioner!) played a major role in this effort to create a behavioural pattern based on a supposedly “Indian moral culture”. In an interview to the New York Times, he is reported to have recommended abstinence from “pre-marital and extra-marital sex” as a better means of avoiding aids instead of using condoms, since such abstinence is “a part of Indian culture”. In yet another effort to reform the sartorial preferences of Indian women, a BJP minister of Goa, Sudhir Davalkar, warned: “Scantily dressed girls (do) not fit in our culture.” Plans are also afoot to revive ‘Indian culture’ by RSS institute Bharatiya Itihas Sankalan Samiti which has laid down guidelines for writing history from our puranas, to cleanse the current history textbooks of “corrupt Western cultural influences”.

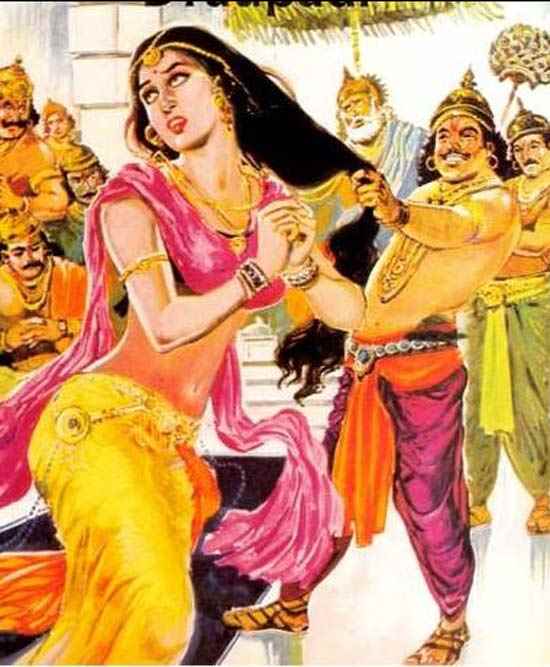

But these views and norms about sexual practices and female behaviour and attire that these venerable gentlemen are propagating and laying down as the one—and only—‘Indian culture’ sanctified by their Hindu religious tradition were flouted by the heroes and heroines of the Mahabharata itself. Most of the heroines did not set much store by the Hindu ideal of female chastity that our ministers would want our women to follow. Going by the explicit description of the beautiful contours of their bodies (quite visible behind their dress) that we find in the epic, they beat hollow the hip-hugging jeans-clad women that the Sangh parivar’s moral guardians are objecting to. As for the heroes of the Mahabharata, they merrily indulged in pre-marital and extra-marital relationships. And let us not forget that they and their children, who were born out of wedlock, were elevated to positions of superheroes.

Birth of the ancestors of Kurus and Pandavas: Without pre-marital and extra-marital sex, which Dr Harsh Vardhan and his party leaders blame as the main cause of our problems, they would not have had their heroes like Veda Vyasa (who wrote the epic), and the sons that he bred through adulterous relationships (Dhritarashtra, Pandu and Vidura), and his grandsons (the five Pandavas). Let us listen for instance to the story of the birth of Veda Vyasa, as described in the Adi Parva of Mahabharata: One day the great sage Parashara, in the course of his pilgrimage, arrived on the shores of the Yamuna river and saw an extraordinarily beautiful woman with a charming smile on her lips, seeing whom he was affected by the excruciating desire of making love to her. The woman happened to be Matsyagandha (her name meaning ‘smelling of fish’, since she was the adopted daughter of a fisherman family), who used to ferry passengers in her boat across the river. When Parashara approached her with his desire, she expressed her inability to immediately satisfy him, drawing his attention to the large number of rishis (sages) waiting on both banks of the river for her to carry them across. Parashara immediately created a fog that immersed the area in darkness—so that the rishis could not see what he planned to do. Although impressed by Parashara’s miracle, Matsyagandha pleaded: “But I shall lose my virginity if I satisfy your desire. How can I then go back to my home, and live in society?” Parashara said: “If you satisfy me, I shall give you whatever you pray for...and restore your virginity.” Matsyagandha prayed: “Please let my body exude a sweet smell.” Having been granted that request, she agreed to sleep with Parashara—and in due course, gave birth to a son who came to be known as Krishna Dwaipayana (meaning dark-skinned and born on an island). Vyasa left home to be an ascetic, but reassured his mother that he would come back to her whenever she needed him.

Sometime later, his mother (now known as Satyavati, her body “sweet-scented” and her “virginity restored”—thanks to Parashar’s blessings) got married to a king called Shantanu. Through him, she gave birth to two sons—Chitrangad and Vichitravirya. After Shantanu’s death, Chitrangad was killed in a battle, and Vichitravirya ascended the throne. He married two sisters—Ambika and Ambalika (both daughters of a king). TheAdi Parva describes how Vichitravirya failed to produce any children, even “after spending seven years with the two queens in continuous vihar (amorous frolic), (following which) he fell victim to tuberculosis in his youth,” and died despite sincere efforts by his friends and doctors. The problem started now. How were the two childless queens expected to carry on the dynasty? Their mother-in-law Satyavati first requested her stepson Bhishma (her late husband Shantanu’s son by his first marriage) to impregnate the two young widows. When he refused, she summoned her own first son Vyasa (who had promised to help her whenever she needed his help)—who was willing to solve the problem. But Vyasa, having followed a rather earthy lifestyle in the forests all these years as an ascetic, looked quite hideous and repelling to the two dainty queens. After being persuaded by Satyavati, her eldest daughter-in-law Ambika agreed to welcome Vyasa to her bed. But then seeing his ferocious countenance from close quarters—dark skin, blood-red eyes and matted hair—she closed her eyes in fear. After completing his required role, Vyasa told his mother Satyavati that although a son would be born endowed with superhuman mental and physical powers, he would be born blind—because Ambika had committed the error of closing her eyes during his conception. That was why Ambika gave birth to the blind Dhritarashtra. In order to correct the effects of the error, Satyavati sought another grandchild in the family who would be perfect this time. She recalled her son Vyasa again, to impregnate the second daughter-in-law Ambalika. But Ambalika again, at one glance at Vyasa’s fearful visage, turned pale—and thus gave birth to Pandu (coloured yellow). Disappointed by getting another imperfect (discoloured) grandson, Satyavati summoned her son Vyasa to again impregnate her first daughter-in-law Ambika. This time, however, Ambika subverted Satyavati’s plans. Refusing to suffer the unwelcome “sight and smells” of the jungle-bred Vyasa, Ambika cheated him by dressing up one of her beautiful slave girls in her own ornaments and sending her to him. Unlike the two queens, this woman, who suffered from no scruples, made love to Vyasa with all abandon, and a happy Vyasa blessed her with the words: “You are henceforth free from slavery, and your son will become extraordinarily wise and extremely pious.” Thus was born Vidura, the most perfect and intelligent of all the three brothers (Adi Parva).

Birth of the Pandavas

The legacy of pre-marital sex, and the practice of producing children through the extra-marital recourse (of requesting or appointing another male to impregnate the wife or widow), known as ‘kshetraja’, continued even after the birth (through such means) of the ancestors of the dynasty that Mahabharata celebrates. It was only thanks to the custom of ‘kshetraja’ that all the later Pandava heroes were born—Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna and the other two inconspicuous brothers (Nakula and Sahadeva)—whom the Sangh parivar worships, and its ideologues are at pains to turn into ‘historical characters’. Let us begin with the story of their mother Kunti. The Mahabharata describes how Kunti, the virgin daughter of a king, satisfied the sage Durvasa when he came to their house as a guest, and obtained from him a blessing that allowed her to summon any god who could impregnate her with their power to produce their respective sons. A young and impulsive Kunti, in order to test the veracity of the blessing, summoned the sun god, who immediately appeared and demanded satisfaction of his desire to sleep with her. Through a cunning combination of persuasion, threat and charm, the sun god seduced a reluctant and fearful Kunti, promising to restore her virginity, and then disappeared in the skies. But Kunti found herself left in the lurch, when she gave birth to a son born of the sun god. Scared of facing social ostracism for her impetuous act, Kunti got rid of her first-born by throwing him into a river. Luckily, a family (belonging to the lower caste of charioteers) picked up the son and brought him up, enabling him to emerge as the powerful warrior Karna (Adi Parva).

After having hidden that act of sexual indiscretion, Kunti reappeared on the scene as a princess, ready to choose her husband from among numerous royal candidates, through a custom called swayamvara (which allowed the woman to embrace a spouse of her own choice from an assembly of candidates). Will the present BJP government—which claims to restore the so-called Hindu traditions—dare to re-establish the custom of swayamvara? To come back to Kunti, in the swayamvara assembly, she tied the garland of flowers around the neck of Pandu, thus announcing her choice of him as her husband. They led a happy married life, till one day Pandu, during a hunting spree, interrupted the mating of a pair of deer by shooting at them with his arrows. The deer were actually a human couple. The husband, who was the son of a sage, had decided that day to take on the form of a stag and transform his wife into a deer, to savour the delights of animal sexuality perhaps! Angered by being stopped mid-way in his adventure, the sage’s son cursed Pandu, predicting that he would die if he ever tried to make love to his wife. An anguished Pandu requested Kunti to conceive through other means, in response to which she made use of Parashara’s old blessing—and summoned, one by one, the gods Dharma, Vayu and Indra, sleeping with whom she gave birth respectively to Yudhishthira, Bhima and Arjuna. Requested further by Pandu to help his other wife Madri to conceive, Kunti summoned the twin gods Ashwini Kumars, who impregnated Madri which led to the birth of the other two Pandavas—Nakula and Sahadeva. The above accounts are from the Adi Parva, the first volume of the Mahabharata—which the Sangh parivar ideologues cannot surely dismiss as figments of a Marxist imagination! What follows in the next 17 volumes of this fantastic epic is a cornucopia of romantic stories, secret intrigues and surreptitious love affairs (with which the main narrative of battles and wars are interspersed) that unfold a variety of sexual lifestyles and inter-caste/racial liaisons (which had made possible the birth of Vidura in the past, and the later romance between Bhima and the forest-girl Hidimba, or the marriage of Arjuna with the Manipur princess Chitrangada).

If consenting adults in India today seek to follow a similar pluralistic lifestyle of multifaceted and multi-integrated romantic relationships cutting across caste/racial/religious lines, it invariably invites violent opprobrium from the parivar. In the rural areas, in the name of preserving the purity of the multi-tiered Hindu caste system, its ideology of ‘Indian culture and tradition’ encourages the khap panchayats to lynch any couple daring to follow the example of Bhima and Hidimba, or excommunicate a modern Vidura as ‘illegitimate’! In the urban areas of India, the same ideology encourages a xenophobic, aggressive bias against people from the non-Hindi-speaking northeast—leading to the rape of today’s Chitrangadas of Manipur in the streets of national capital Delhi.

Sangh parivar sants and BJP politicians in the role of gods of the epics: As for the heroes and heroines of Mahabharata, the ideologues of the Sangh parivar may explain away their acts of pre- and extra-marital sex, inter-caste or inter-racial relationships, as blessed and sanctioned by the gods. But since those divine progenitors of the Pandavas—Dharma, Vayu and Indra—have failed to reappear in modern times, the Sangh parivar appears to be creating their human counterparts in the shape of godmen and MPs and mlas. We thus find characters like Asaram Bapu and his son Narayan Sai from north India, and Nithyananda from south India—all close to the parivar—taking on the role of gods to seduce their female devotees with the promise of divine salvation. They are facing criminal charges in the courts. Then, there are the BJP ministers and leaders, like Nihal Chand Meghwal (Union minister of state for chemicals and fertilisers), Krishnamurti Bandhi (BJP MLA from Chhattisgarh) and Madhu Chavan (BJP leader from Maharashtra) among many others—who have been accused of rape. They can perhaps be seen by the followers of Sangh parivar as reincarnations of the all-mighty rishis of the past (Parashara, Durvasa and others who could always get their own way by threats or curse), and as a privileged lot like them, can pick up any female of their choice, and—because of their present political clout—can silence their victims and their families with threats of elimination.

Given this reality, the present BJP-led government and its ideologues will have to make up their mind about the Mahabharata. Since they revere the heroes and heroines of the epic, and want to prove that they were historical characters, they should permit the common citizens to emulate the liberal lifestyle that they led. But then, what happens to the Sangh parivar’s grandiose plan of creating “a morally pure Hindu” society populated by sexually constipated men and women? In order to overcome this embarrassing dilemma, the BJP government and its RSS mentors have two options. One, in obeisance to both the female and male deities and and mortals who are described in the epic as following a rather permissive sex life, they should scrap their own programme of imposing rules and restrictions for the man-woman relationship, ignore cases of pre-marital sex or relationships between consensual partners, and stop branding inter-religious liaisons like a Muslim boy’s love affair with a Hindu girl as ‘love jehad’. The other option is banning the Mahabharata in its original version altogether—so that the public does not have access to the full text. The RSS historians can bring out, instead, sanitised editions of the epic that blot out the explicitly described stories of the promiscuity of their deities and the birth of their heroes and heroines.

(Sumanta Banerjee is a cultural historian who specialises in research into popular culture, particularly of the colonial period. He is the author of many books, including The Parlour and the Streets: Elite and Popular Culture in Nineteenth Century Calcutta.)

The stories of the Mahabharata, for instance, are often at odds with the Hindutva that the BJP government and its parent Sangh parivar preach. Although the votaries of Hindutva worship the epic’s heroes and heroines, the messages that most of the latter impart may not be suitable for the present government’s programme to educate our people in the “moral and cultural values” that they want to uphold in the name of Hindutva. In fact, the deities and mortals described in the eighteen volumes of this hefty tome had never once been designated by the term ‘Hindu’. The Mahabharata may turn out to be a rather uncomfortable quarry for the BJP ministers and Sangh parivar historians to dig up models to suit a Hindu-specific Indian ideal of morality and culture.

The just-replaced health minister Harsh Vardhan (a medical practitioner!) played a major role in this effort to create a behavioural pattern based on a supposedly “Indian moral culture”. In an interview to the New York Times, he is reported to have recommended abstinence from “pre-marital and extra-marital sex” as a better means of avoiding aids instead of using condoms, since such abstinence is “a part of Indian culture”. In yet another effort to reform the sartorial preferences of Indian women, a BJP minister of Goa, Sudhir Davalkar, warned: “Scantily dressed girls (do) not fit in our culture.” Plans are also afoot to revive ‘Indian culture’ by RSS institute Bharatiya Itihas Sankalan Samiti which has laid down guidelines for writing history from our puranas, to cleanse the current history textbooks of “corrupt Western cultural influences”.

|

Birth of the ancestors of Kurus and Pandavas: Without pre-marital and extra-marital sex, which Dr Harsh Vardhan and his party leaders blame as the main cause of our problems, they would not have had their heroes like Veda Vyasa (who wrote the epic), and the sons that he bred through adulterous relationships (Dhritarashtra, Pandu and Vidura), and his grandsons (the five Pandavas). Let us listen for instance to the story of the birth of Veda Vyasa, as described in the Adi Parva of Mahabharata: One day the great sage Parashara, in the course of his pilgrimage, arrived on the shores of the Yamuna river and saw an extraordinarily beautiful woman with a charming smile on her lips, seeing whom he was affected by the excruciating desire of making love to her. The woman happened to be Matsyagandha (her name meaning ‘smelling of fish’, since she was the adopted daughter of a fisherman family), who used to ferry passengers in her boat across the river. When Parashara approached her with his desire, she expressed her inability to immediately satisfy him, drawing his attention to the large number of rishis (sages) waiting on both banks of the river for her to carry them across. Parashara immediately created a fog that immersed the area in darkness—so that the rishis could not see what he planned to do. Although impressed by Parashara’s miracle, Matsyagandha pleaded: “But I shall lose my virginity if I satisfy your desire. How can I then go back to my home, and live in society?” Parashara said: “If you satisfy me, I shall give you whatever you pray for...and restore your virginity.” Matsyagandha prayed: “Please let my body exude a sweet smell.” Having been granted that request, she agreed to sleep with Parashara—and in due course, gave birth to a son who came to be known as Krishna Dwaipayana (meaning dark-skinned and born on an island). Vyasa left home to be an ascetic, but reassured his mother that he would come back to her whenever she needed him.

|

The legacy of pre-marital sex, and the practice of producing children through the extra-marital recourse (of requesting or appointing another male to impregnate the wife or widow), known as ‘kshetraja’, continued even after the birth (through such means) of the ancestors of the dynasty that Mahabharata celebrates. It was only thanks to the custom of ‘kshetraja’ that all the later Pandava heroes were born—Yudhishthira, Bhima, Arjuna and the other two inconspicuous brothers (Nakula and Sahadeva)—whom the Sangh parivar worships, and its ideologues are at pains to turn into ‘historical characters’. Let us begin with the story of their mother Kunti. The Mahabharata describes how Kunti, the virgin daughter of a king, satisfied the sage Durvasa when he came to their house as a guest, and obtained from him a blessing that allowed her to summon any god who could impregnate her with their power to produce their respective sons. A young and impulsive Kunti, in order to test the veracity of the blessing, summoned the sun god, who immediately appeared and demanded satisfaction of his desire to sleep with her. Through a cunning combination of persuasion, threat and charm, the sun god seduced a reluctant and fearful Kunti, promising to restore her virginity, and then disappeared in the skies. But Kunti found herself left in the lurch, when she gave birth to a son born of the sun god. Scared of facing social ostracism for her impetuous act, Kunti got rid of her first-born by throwing him into a river. Luckily, a family (belonging to the lower caste of charioteers) picked up the son and brought him up, enabling him to emerge as the powerful warrior Karna (Adi Parva).

After having hidden that act of sexual indiscretion, Kunti reappeared on the scene as a princess, ready to choose her husband from among numerous royal candidates, through a custom called swayamvara (which allowed the woman to embrace a spouse of her own choice from an assembly of candidates). Will the present BJP government—which claims to restore the so-called Hindu traditions—dare to re-establish the custom of swayamvara? To come back to Kunti, in the swayamvara assembly, she tied the garland of flowers around the neck of Pandu, thus announcing her choice of him as her husband. They led a happy married life, till one day Pandu, during a hunting spree, interrupted the mating of a pair of deer by shooting at them with his arrows. The deer were actually a human couple. The husband, who was the son of a sage, had decided that day to take on the form of a stag and transform his wife into a deer, to savour the delights of animal sexuality perhaps! Angered by being stopped mid-way in his adventure, the sage’s son cursed Pandu, predicting that he would die if he ever tried to make love to his wife. An anguished Pandu requested Kunti to conceive through other means, in response to which she made use of Parashara’s old blessing—and summoned, one by one, the gods Dharma, Vayu and Indra, sleeping with whom she gave birth respectively to Yudhishthira, Bhima and Arjuna. Requested further by Pandu to help his other wife Madri to conceive, Kunti summoned the twin gods Ashwini Kumars, who impregnated Madri which led to the birth of the other two Pandavas—Nakula and Sahadeva. The above accounts are from the Adi Parva, the first volume of the Mahabharata—which the Sangh parivar ideologues cannot surely dismiss as figments of a Marxist imagination! What follows in the next 17 volumes of this fantastic epic is a cornucopia of romantic stories, secret intrigues and surreptitious love affairs (with which the main narrative of battles and wars are interspersed) that unfold a variety of sexual lifestyles and inter-caste/racial liaisons (which had made possible the birth of Vidura in the past, and the later romance between Bhima and the forest-girl Hidimba, or the marriage of Arjuna with the Manipur princess Chitrangada).

|

Sangh parivar sants and BJP politicians in the role of gods of the epics: As for the heroes and heroines of Mahabharata, the ideologues of the Sangh parivar may explain away their acts of pre- and extra-marital sex, inter-caste or inter-racial relationships, as blessed and sanctioned by the gods. But since those divine progenitors of the Pandavas—Dharma, Vayu and Indra—have failed to reappear in modern times, the Sangh parivar appears to be creating their human counterparts in the shape of godmen and MPs and mlas. We thus find characters like Asaram Bapu and his son Narayan Sai from north India, and Nithyananda from south India—all close to the parivar—taking on the role of gods to seduce their female devotees with the promise of divine salvation. They are facing criminal charges in the courts. Then, there are the BJP ministers and leaders, like Nihal Chand Meghwal (Union minister of state for chemicals and fertilisers), Krishnamurti Bandhi (BJP MLA from Chhattisgarh) and Madhu Chavan (BJP leader from Maharashtra) among many others—who have been accused of rape. They can perhaps be seen by the followers of Sangh parivar as reincarnations of the all-mighty rishis of the past (Parashara, Durvasa and others who could always get their own way by threats or curse), and as a privileged lot like them, can pick up any female of their choice, and—because of their present political clout—can silence their victims and their families with threats of elimination.

Given this reality, the present BJP-led government and its ideologues will have to make up their mind about the Mahabharata. Since they revere the heroes and heroines of the epic, and want to prove that they were historical characters, they should permit the common citizens to emulate the liberal lifestyle that they led. But then, what happens to the Sangh parivar’s grandiose plan of creating “a morally pure Hindu” society populated by sexually constipated men and women? In order to overcome this embarrassing dilemma, the BJP government and its RSS mentors have two options. One, in obeisance to both the female and male deities and and mortals who are described in the epic as following a rather permissive sex life, they should scrap their own programme of imposing rules and restrictions for the man-woman relationship, ignore cases of pre-marital sex or relationships between consensual partners, and stop branding inter-religious liaisons like a Muslim boy’s love affair with a Hindu girl as ‘love jehad’. The other option is banning the Mahabharata in its original version altogether—so that the public does not have access to the full text. The RSS historians can bring out, instead, sanitised editions of the epic that blot out the explicitly described stories of the promiscuity of their deities and the birth of their heroes and heroines.

(Sumanta Banerjee is a cultural historian who specialises in research into popular culture, particularly of the colonial period. He is the author of many books, including The Parlour and the Streets: Elite and Popular Culture in Nineteenth Century Calcutta.)

No comments:

Post a Comment